Serving Scotland's people

As fundraising efforts continued, St John Scotland began to put its hard-earned funds towards good causes that served older and vulnerable people across Scotland. Throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, the organisation built and operated hospitals, care homes and accommodations. In later years, St John Scotland’s local Area committees supported other charities and organisations that were meeting local needs. This included, from the 1990s onwards, developing an enduring relationship with Scottish Mountain Rescue, which has seen St John Scotland become the biggest charitable donor to the teams, providing funds for vehicles and bases across the country.

In addition to its core services, which will be explored in the next section of this website, St John Scotland continued to support the St John Eye Hospital in Jerusalem, and more recently became involved with St John Malawi to provide effective healthcare in one of Africa’s poorest countries.

Always seeking to help those in need, St John Scotland’s members have delivered some remarkable results over the past seventy-five years. Read on to learn about some of those activities.

THE ST JOHN HOSPITALS

1st September 1947 saw the opening of the Order of St John Foundation Hospital at 7 Park Circus Place, in Glasgow. The Foundation Hospital was organised:

… for the benefit of the ‘black coated’ section of the community, without distinction of class, race or creed. The poor are very adequately catered for in the general hospitals, while the rich are usually able to make such arrangements as they require. Unfortunately, those of moderate means have often been unable to receive treatment under the conditions best suited for their speedy recovery.

Order of St John Foundation Hospital, 7 Park Circus Place, Glasgow

Fees were set within the means of those with relatively moderate incomes. A Linen Guild organised the supply and maintenance of all napery, bedding, cutlery, crockery and kitchen utensils. The first hospital functioned until December 1956 when the organisation opened a new one, the St John Foundation Hospital, known as Park Home, in 12 Claremont Terrace, Glasgow, in a building gifted to the Order. The new hospital was operational until 1966, by which time the upgrading of National Health facilities in Glasgow had resulted in it hospital being underused. The organisation had never charged patients the full cost of their treatment and with low occupancy, losses could no longer be sustained.

In May 1949, the organisation acquired the Armstrong Nursing Home at Albyn Place, Aberdeen, which had an attached nurses’ residence, and immediately renamed it the St John Nursing Home. Funded solely by private individuals rather than the public, St John ran the nursing home with some charity beds, eventually developing it into a full-scale hospital. In 1973, the Aberdeen nursing home was enlarged to provide a new operating theatre and ten private rooms. Operating difficulties and a subsequent drain of financial resources forced the organisation to make difficult financial decisions, which led to the sale of the St John Hospice at Lossiemouth to raise funds.

St John Nursing Home, Nos. 21, 22/23, and 24 Albyn Place

The house on the right was gifted to the Aberdeen Committee of the Order by Mrs J A Ross, OStJ. The ancient St John’s Well, which was formerly sited in Gilcomston, is on the bottom left of the photograph.

Notwithstanding, another major extension was constructed and the new facility, now named St John Hospital, was officially opened by the Duke of Gloucester in 1987.

The 1980s was a time of huge expansion for Aberdeen and the hospital benefitted from an increase in business from the thriving oil and gas industry. However, in 1995, St John Hospital was sold to a management buyout and its name was changed to Albyn Hospital. The sale came as a huge shock to Association members and staff alike:

To have the staff of the hospital who knew it was owned by St John, discover from the local radio or from the Evening Express newspaper that the hospital had been sold, it was a disaster. They were in tears, they didn’t know where to look, what to say, it was a terrible, terrible thing to happen and hopefully a very large lesson was learned from that. Even the local Association Committee had no idea, they were kept totally out of it, so it did not go down well. They sold it to the General Manager, who in turn within two years sold it on for double the price. However, the money that came in from the hospital, we believe, was the start of the real money in St John Scotland; we think that is the nucleus that has been built on, so it served a very good purpose.

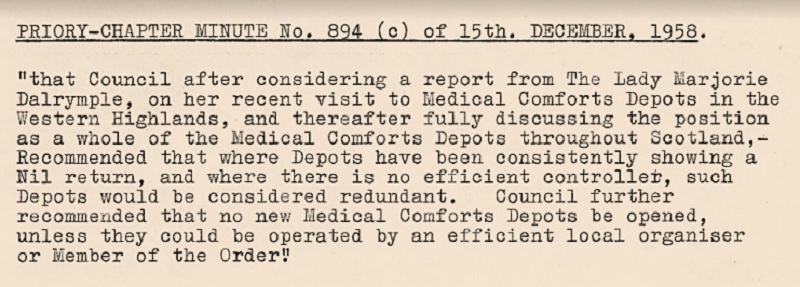

MEDICAL COMFORTS DEPOTS

Twenty Depots were opened during the organisation’s first year and another eleven in the next year. The first Depot was opened in Hamilton and was quickly followed by others in Inverness, Isle of Skye, Jura, Kirkcudbright and St Andrews. These Depots were places where anybody could borrow commodes, crutches, bed rests and other aids. However, with the advent of the National Health Service, the provision of such resources became the responsibility of local health authorities and use of the depots dwindled (see below). By the late 1960s, the service ended.

HOMES FOR OLDER PEOPLE AND PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

The first of St John Scotland’s homes for older people was opened on 4th October 1950, at Carberry. The primary purpose of St John's Hospice for Elderly People, near Musselburgh, was to provide short-term holiday accommodation for up to ten guests during the summer, and longer-term rest during the remainder of the year.

The Carberry hospice (pictured on next page) was not always used to full capacity and, in 1981, it was closed after it had become increasingly expensive to maintain.

Margaret Balfour recalls helping to raise funds for the residential homes. When she left school in 1962, Margaret helped her aunt serve coffees at the Autumn Fayre, and her involvement with St John Scotland snowballed from there:

The fayres were to raise funds for the St John’s homes in Lennox Row in Edinburgh, and in the grounds of Carberry Towers. Although the homes were residential, the original idea was for people coming out of hospital and needed a bit of convalescing before they went home to their own house. It was supposed to be a maximum of six weeks they stayed for; sometimes it stretched, it could be less, it could be more. If an elderly relative stayed with relations, they could go in there for a little holiday.

When the Carberry hospice was later sold, Margaret remembers that St John Scotland used the capital from the sale to purchase another property. After viewing several premises, the organisation settled on the house at Cramond and ran this jointly with Alzheimer's Association Scotland.

For over thirty years, Margaret and other volunteers also raised money through St John Scotland’s charity shop. She was Convenor of the shop, working there Thursday, Friday, and Saturday, along with two young women who were participating in the Duke of Edinburgh Awards Scheme. The St John team also continued to raise funds through their various fayres, and volunteers did house-to-house collections in Musselburgh every week. They raised enough funds for minibuses, defibrillators, Mountain Rescue teams, and supported the ‘Talking Newspapers.’

We had a very successful 30th birthday party for the volunteers from the shop, and we were able to hold it at the house in Cramond, in 1999.

The St John Home, ‘Lindores’, Cramond

In cooperation with the Lothian Hospitals NHS Trust, the Cramond Home accommodated people from south-west Scotland who needed treatment at the Oncology Unit in the Western General Hospital, Edinburgh. Although out-patients, these people needed accommodation as they lived so far away but the only other accommodation on offer would be in a hospital ward. The project was operated in conjunction with St John Scotland’s Dumfries and Galloway Area, who helped to transport the patients to and from Edinburgh. The patients benefited from the homely atmosphere of the comfortable house and its tranquil, semi-rural setting and were very appreciative of the service, particularly at such a difficult time for them and their families.

The next home emerged from the Edinburgh Home for Working Mothers with their Children. St John Scotland initially undertook to manage the home on behalf of a society; however, there was little demand for the service by that time and the owners decided to disband and sell the building. The organisation then bought it and began to operate it as a holiday home similar to the one at Carberry.

In 1957 a house named Skerry Brae near Lossiemouth (now a hotel and restaurant; pictured below) was gifted to St John by Mr G Boyd Anderson, Commander of the Order, to be used as a holiday home in summer and a convalescent home in winter. Later the building was adapted for use as a conference centre in winter, while remaining a holiday home in summer.

In 1977, the Fife St John Association opened the Old People’s Holiday Flat in Leven as a venue for the elderly. This was followed two years later by St John Central Area’s creation, in Strathyre, of Sir Andrew Murray House, Holiday Home for the Blind, Disabled and Elderly. The latter, a purpose-built holiday home, was a major undertaking, which cost £50,000 at the time. It was designed and equipped for older people and holiday guests with physical disabilities.

Set amidst some of Scotland’s most scenic country, in the village of Strathyre, the accommodation consisted of four double rooms with private bathroom and kitchen, and one unit with two rooms, each with two single beds, bathroom and kitchen. There was also a comfortably furnished communal lounge, a large conservatory and a games room.

Sir Andrew Murray House

The Strathyre home offered opportunities for other charities to provide holidays for their clients at reasonable cost. Unfortunately, over a number of years, there was a steady decline in clients, so Chapter (the Board) took the decision, in August 2012, to close the facility as no longer sustainable.

Unfortunately, many of the holiday homes were not viable in the long term due to the reasons outlined above – declining visitor numbers, and new requirements to improve fire and safety standards and equipment, of which the cost of upgrading when balanced with the potential return was found to be unfeasible. Skerry Brae also suffered the disadvantage of being comparatively isolated, especially once the rail service began to diminish following the widely lamented Beeching cuts, which was a plan to increase the efficiency of the nationalised railway system in Great Britain. The eventual outcome was that St John Scotland decided to cut its losses and the short-stay homes were gradually sold.

It may be argued that, since 1947 St John Scotland had shown flexibility in adapting to changing social needs and circumstances. When one service became redundant, attention was turned toward a different area of concern. In selling the short-stay premises, the organisation freed up time, funds and energies, thereby allowing members and volunteers to explore new ways of helping those in need.

In October 1975, the St John (Glasgow) Housing Association opened St John Court in Partickhill. This was a first for St John Scotland - the provision of sheltered housing. St John’s Court (pictured below) is located in an attractive residential part of Glasgow’s west end where shops and public transport are nearby. The sheltered housing accommodation provided for twenty-five tenants in self-contained flatlets. Each had a bed/sitting room, a kitchenette and a bathroom, and a resident warden stayed in the premises. Tenants were able to retain their independence and privacy whilst also being able to access the company of other residents when they wished.

Iain Smith’s involvement with St John Scotland was largely with the St John (Glasgow) Housing Association. He remembers that “The building was perfect, purpose built, big wide corridors, full double-glazed windows, good ventilation throughout the building.” Iain thought St John Court was ideal for residents:

This was one of the great benefits of this communal living in that the warden was the key to dreaming up ideas like bus runs. It wasn’t weekly. There wasn’t an Entertainments Officer like they have now in a care home, but if you got a sparky warden, they would organise indoor carpet bowling, quizzes, bridge, social afternoons, and a film. I remember one time, my wife and I enjoy dancing, and I remember we brought along our ceilidh band from Bearsden Church one Christmas, and they played for a sing-along, all the old favourites, and we’d take our children along and the residents just loved these tiny tots roaming. These are the touches you cannot buy. It was very nice times.

Opening of St John’s Court, Glasgow,

by the Grand Prior, HRH The Duke of Gloucester

11th October 1975

The Association managed the premises and the running of the complex quite successfully but over time, members became frustrated and then concerned at the changes to care regulations and visits by care regulators:

Oh yes, and these [visits] accelerated from probably an annual casual visit in the mid [19]70s when I joined, and these were just checking that the residents were happy, the building was safe and that the support to those subsidised residents’ rents was being properly managed. That accelerated dramatically from the mid- [19]80s through to the turn of the century, so that these visits were becoming far more serious, far more emphasis on safety. We were looking after more vulnerable people, therefore we had to adhere to more strict regulations about training for the warden and all the procedures regarding managing the place, so we had a wall full of policies eventually. Now, in the early stages you can manage that with a volunteer management committee, a warden and a paid secretary, like in this case, the solicitors, but the minute you go into constant rewriting of policies and what have you, the warden can’t do it, so it starts to be hard work for the volunteers and that was not fair on the volunteers, so the pressure was growing. It was very gradual at first but towards 2003/2004/2005, we were under a lot of pressure that we would be better served - the residents wouldn’t necessarily be better served because they were happy, and in all the reports that came up they couldn’t be happier, they loved it as it was, that was important – but from a regulation point of view it was obvious that the powers that be really thought that we should be part of a bigger group. There was no connection between us and the other St John houses, which were more care home orientated, whereas we were, as I said, sheltered housing; and it was very sheltered, and you got on with your own business. So that’s the pressure of policy making and Government controls, and a lot of the Government controls were well meaning but involved a lot of bureaucracy, and involved added pressure on people who don’t sign up to that when they initially said, ‘I can help out here.’

Meanwhile, more homes had been opened in Glasgow, including St John Residential Home, 23 Mansionhouse Road, Langside. It is now classed as a Category B listed building. John Ford recalls:

I noticed that things were happening in St John, and Bill Gordon kept on telling me about it, and then he told me they were opening a home in Langside, in Glasgow. He was the Chairman of the Committee that was looking after it and he wanted me to be on the Committee and I said, ‘No, I can’t’. Then he wanted me to do some cleaning there [John was at this time an Administrator for Office Cleaning Services] and I went out and had a look at it and said, ‘Yes, I think we can do that… You need every assistance you can get here.’ So, we waived the charge, and he was very grateful for that. He still wanted me on the Committee, but I couldn’t do it; business was everything at that time and we were really busy and doing quite well really.

St John Residential Home, Langside

John did join St John Scotland a few years later:

[St John] Glasgow by that time had a home in Langside, a home in Newton Mearns, and it had a sheltered housing complex in Partickhill in Glasgow, all run by the Committee. And of course, the St John Associations were the workhorses… they were the people who did all the work at the functions, etc. Glasgow was very fortunate, there were lots of ladies, wives of members who were so enthusiastic, they ran these homes.

I always felt very privileged they wanted me to be Chairman. Ewan Murray was a devoted Secretary, and he and I got on very well. One day Ewan Murray came in and said we’ve got to sign a new contract with Glasgow City Council for the transfer of people coming into our homes. They would send people to live in our homes. I was quite concerned because of all the conditions, and the document was so thick it was unbelievable, but the responsibility for this really came down to me and at the end of the day, the buck stopped with me. And I was really a bit concerned about this. And I spoke to Jim Brown, who said, ‘Oh, don’t worry about this, it’s not been a problem before’. But we had two committees, a committee to run the Langside home and a committee to run the Newton Mearns home, a house that had been donated to the Order by a family called Ross. These homes were superb, run very well indeed by the staff there and supervised by our committees. The sheltered housing complex had a board of directors.

Discussing the Partickhill complex, Iain Smith was asked whether the site closed down. Iain replied:

We didn’t close down; we formally transferred the management and ownership of the site to Loretto Housing Association in 2009. I joined in 1987 and 22 years later I said goodbye. The reason for that was back to this pressure that we were under, but the Government said, ‘No, no, we’ve got two or three very committed Care Home Managers that we think should sit on your committee, whether you like it or not.’ So, they came and sat on our committee and gave us advice; but it was clear it wasn’t advice, they were scheduling to get us transferred to a part of a bigger organisation. So, after a year they had been scurrying around in the background and said, right here you can either join them, them, or them, and so… we chose Loretto Housing. We had 25 flats and they had something like 2,000, everything from care homes to sheltered housing, to social housing. So, they were a big landlord and well set up and at the end of the day with all the pressure it was a great relief to everybody. By this time, the committee was down to about five or six, or four or five, and were quite glad to see the back of it. So, it was a shame and what disappointed me most was the happiness we were leaving behind that we had created, and it couldn’t possibly be the same after that.

John explained that Glasgow and all the areas at that time looked on themselves as individual units, raising and spending their own money, and St John Scotland’s headquarters had little involvement. With the new rules and regulations surrounding homes coming into force, the Chapter (Board) discussed the problem:

We raised the problem about these homes, and it was quite obvious that we were going to have to get out of this, that it was going to be a real problem, and eventually that happened. We closed down Langside and were able to get every one of the patients, customers, clients, well suited and placed. It was all done in a very good way; it was amazing how it happened… We had this one in Newton Mearns, which we tried to change into a day centre for respite care coming in. We spent a huge amount of money adapting it and were promised help from East Renfrewshire and Glasgow who had been sending people, but in the end they didn’t [help], as by that time they had started developing things of their own… so eventually, after our huge expense, it had to be sold off… At the same time OSCR, the regulator for charities, was coming into operation and we had to adapt accordingly. That was in the [19]90s and James Stirling became Prior, and he had seen what was coming.

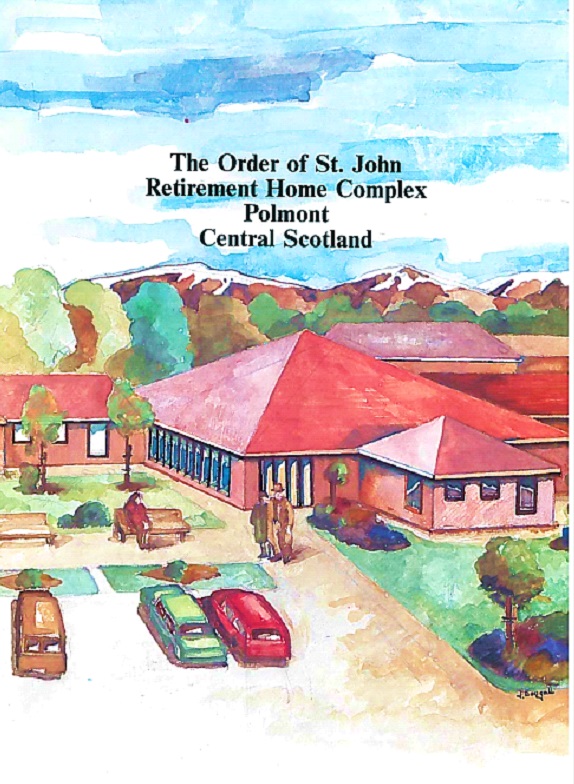

During this same period, a St John retirement complex, named Archibald Russell Court, was opened at Polmont. This eleven-flat complex was completed in November 1993. Each flat had two bedrooms, a lounge, kitchen, and bathroom. Patio doors from the lounge opened onto large, professionally landscaped gardens. A separate residents’ lounge provided a friendly meeting place for residents and friends. The complex had gas central heating, a modern security system and a caretaker service. David Waddell and his wife, Charlotte, recall how a waiting list was established and how management of the complex was problematic for an inexperienced management team:

Initially, I think there was a convenor for Polmont, and I think if he liked you, you got in, but that had to change. So, we had to get a waiting list and people were on the waiting list and the person at the top was offered the flat. This had to change because of OSCR, they were better at flexing their muscles in those days, so that was something else I had to do, but that was how it was before.

[There was] a Management Committee, which consisted of Archie [Russell] as Chairman, myself as Secretary, the Treasurer, and the Convenor, but things were very much left to the Convenor and that was just the way it was. When I took over, it wasn’t the fact that I felt things had to change, not just because I wanted them to change, but because the world had changed. There was legislation. I remember getting a flyer in from the gas board saying this change in law was taking place from next April, we’re happy to come in and do the work for you. I had no idea; we didn’t have any expertise in our Management Committee... I was in my seventies and some of them were older than that. And it always bothered me that if anything happened, if there was a fire and somebody was injured, or worse still, lost their life, the press would have a field day. It never happened, fortunately, but that was always what the concern was. So, after the restaurant conversion and all this happening, everything had to be more organised, and that’s when we moved to proper waiting lists and everything being done properly.

I was Secretary for seven years when David was Chairman. I worked in the little office up the stair; there was all sorts to do. Archibald Russell Court was in place, of course, by that time, and it was all run on a voluntary basis, so there was a great deal of toing and froing with things to be seen to. I think we took fright eventually when the firemen did their annual audit and they spoke about fire doors and all the rules being changed. And we came to realise that the layman doesn’t know what was required, and it’s a responsibility, with all the elderly people being in the accommodation. That was when we went to Bield to run it; as that was their line of business, they knew about the new rules and could carry them out.

The Archibald Russell Court retirement complex at Polmont is still owned by St John Scotland but it is now managed by Bield Housing and Care on their behalf.

Douglas Dow, an experienced lawyer, was asked about the properties that were disposed of overtime by the organisation:

Basically, over the years, the Order of St John in Scotland was donated properties of all kinds by wealthy people. One of the things that was donated to the Order was bits and pieces of property in the Aberdeen area, in Aberdeen itself, buildings and so forth, and they joined up together to form a private hospital, in effect, which was run under the name of the Order of St John. And I think there were concerns that people were paying fees for treatment in this private hospital, and these fees were going to the Order of St John. And the issue, I think, from a tax point of view, was whether this was a charity, or was not a charity but actually a trading entity. It was decided, this was before my time, it was decided to sell this private hospital in Aberdeen, and they did, for millions of pounds, and that really is the core of funds that we have today for what we need.

I mentioned to you all this money we got coming in from Aberdeen. Well, we didn’t sit on it. Sir James Stirling, who was the Prior at that stage, said, ‘We can’t just sit on all this money, can we not do something with it?’. And he had interests and connections with hills and mountains, so we started supporting Scottish Mountain Rescue, and we bought and provided Mountain Rescue stations for a whole series of Mountain Rescue teams in Scotland. These stations had, typically, parking, storage, and all the rest of it. Subsequent to that, we’ve now given all these to these [teams] because, again, we were paying all the insurance money and things and we were partly responsible for them, but didn’t have any control over them. We also supported Mountain Rescue by giving them specially adapted Land Rovers for use by the teams, and there’s a scheme for that. So, we haven’t been sitting on the money doing nothing; it’s being used all the time.

With regard to the properties that we had, we had over the years acquired a number of homes, old Victorian houses, which were used as retirement homes and they got harder and harder to operate with all the new rules and regulations, so we got rid of those. That was really before my time. However, we were left with odd bits of land and what we got rid of in my time, recently, was we had two large plots of ground at Carberry Towers in East Lothian. We sold them for around £130,000 and that made sense because these were pieces of land with large trees, some of which were falling or stopped from falling by hitting the other trees, and it was full of dog walkers, and we couldn’t really build on it, so we got rid of those because there was a big risk there. We also had a property, which we had built, called Andrew Murray House, which was at Strathyre, which was a house originally for blind people and was tied in with Erskine Hospital. So, we eventually had this house that was costing us a fortune to run, so we got rid of that. We also sold a plot of ground there at Strathyre, and we had a plot of ground in Glasgow, which we sold. So, all of that went, and we gifted some plots of ground at Strathyre. We gifted them because it became clear that the lady who had gifted a lot of ground at Strathyre had wanted these particular bits of ground to be available for use by the locals. So, we couldn’t really sell them for profit [so we] donated it to them. We also have the [former charity] shop in Edinburgh that we lease out; it’s a commercial outlet and makes a good rental for us.

SCOTTISH MOUNTAIN RESCUE

By the 1990s, St John Scotland was turning its focus to support other organisations providing valuable services locally, including significant support for Scottish Mountain Rescue teams, to which they have provided funds for vehicles and bases to allow them to carry out search and rescue work more effectively. Funds have financed the purchase, adaptation or new build of Mountain Rescue bases, and essential vehicles and equipment, including Land Rovers and radios.

Lawson Rennie was involved with the Ski Rescue Service at Glenshee, which was also funded by St John Scotland, and from that became involved with St John and Scottish Mountain Rescue:

My first involvement with St John Scotland was with Mountain Rescue and Ski Patrol up in Glenshee. St John partially funded the Ski Rescue Service there and I was one of the ski patrollers, and I ended up actually being in charge of all the ski patrollers at the time, mainly because I could get most weekends off and I could get up there. I was living in Dundee at the time, I wasn’t very far away

In those days it was Venture Scouts that we used, and it was a free service to the public. There were two different venture units came along every weekend and, basically, we split them up into teams and they skied the various pistes, basically looking for accidents.

They also had radio, so if anything was reported in to us, we could send the nearest team to them to bring the patient down off the hill. We had our own ambulance at the time, and we took the patient, usually down the hill, to the Spittal of Glenshee Hotel and sort of left them there for the public service ambulance to come up and pick them up, because the public service ambulance had to come up from Blairgowrie, pick up the patient, and then take them down to Bridge of Earn Hospital, unless it was a very serious injury, in which case we would call in a helicopter.

Lawson explains that all of the rescuers had basic first aid training before joining the ski patrol, and the ski patrol staff trained the recruits in the use of specialised equipment, specialised splints, and stretchers. A couple of ski instructors ensured that everyone were competent skiers, and a mountain climbing instructor taught them snow and ice climbing.

We would arrive at the rescue post as soon after half past eight as we could, depending on the weather and the road conditions. We would check out all the equipment, make sure all the emergency bags had all the proper equipment in them, and then split the teams up into various sectors depending on if all the tows were running or not, and not all the tows were running due to lack of snow. The teams would go out and start patrolling. They would look on the pistes to make sure there was no big holes or anything that could be of a danger, in which case the chairlift staff themselves would come along and sort a piste out. Otherwise, they would just free-ski until an accident happened. Sometimes we could get virtually no accidents at all. Saturday was usually fairly quiet, but Sunday was chaotic. Some weekends we could have maybe fifty accidents, not all broken legs, some dislocated shoulders or broken arms, and minor things that could be taken away by themselves and have to go by ambulance, depending again on the snow conditions… In the early [19]90s the chairlift company decided that they would get professional people in themselves. Some of the ski Instructors and some of the tow operators are the actual ski patrollers now. One or two St John people did stay on but most did not.

Gordon Casely talked about the origins of the relationship between Mountain Rescue and St John in Scotland:

It was peculiarly an Aberdeen involvement. Pioneers had thought about Mountain Rescue, which back in the 1960s was still the local bobby and a couple of gamekeepers. It was that kind of thing. Bill Marshall, a great mountaineer, and who became a member of the Order, was my mentor in Mountain Rescue and who got me involved in it, he was looking around for funding. They were desperately poor, providing all their own gear and equipment. And Tony Wyness got involved, as well, and brought the Order’s focus in Aberdeen on to Mountain Rescue. So, it was a meeting of minds, a meeting of charitable minds, and a meeting of active money-raising minds, and it really was a welcome collision. And out of Aberdeen’s pioneering efforts, St John Scotland today is a serious backer of more than two dozen Mountain Rescue Teams, in funding headquarters for them, and vehicles, and equipment. We’re talking big money. When, fifteen years ago, Aberdeen Mountain Rescue Team had a base set up, opened by the Duke of Gloucester, the cost then was a quarter of a million pounds for a fairly basic set up. So, it’s no small beer now, it’s a major business.

Mario Di Maio has been involved with Scottish Mountain Rescue in Aberdeenshire for over fifty years and is hugely appreciative of the support given by St John Scotland.

I joined the Rescue Team in June 1970 and met the then Team Leader, Bill Marshall, who really was the founding member of the Aberdeen Mountain Rescue Team, and he did that through an organisation which was the Aberdeen Venture Club, which was really an organisation designed to give, predominately young lads but also some lasses, as well, the opportunities to get into outdoor-type activities. At that point there were very few Mountain Rescue teams around. This was the mid [19]60s, and in 1964 Bill decided that there was a sufficiently effective group of young folk in this organisation and he could mould them into a Mountain Rescue Team; and in 1964, a formal Mountain Rescue Team was formed, but as you can imagine it was very basic. They didn’t have any real Mountain Rescue equipment; they didn’t really have very much in hill equipment. And Bill spent a lot of time and effort and energy in gathering together from various local sort of people that he had contacts with, either getting bits and pieces of equipment, or gathering some money to get equipment. At that point he made an approach to the Order of St John because we were looking, basically, for somewhere that we could use as a base, and that wasn’t all that easy to find at that time around Aberdeen. And through a connection in the Order at that point, we got access to a garage at the bottom of what was the St John’s Hospital in Albyn Place, Aberdeen. Albyn Lane runs parallel to Albyn Place and there was a small, basically a one-vehicle garage, there, and it had a sort of upper floor; so, we stowed a vehicle there, and the upper floor became the meeting room for the team. It was very basic and my memories of it when I joined the team was that in winter it was really very cold, there was no heating in it apart from a one-bar electric fire. So, when we had our team meetings, I mean everybody sat with all their clothes on, big jackets and all the rest of it, because it was so bitterly cold, but it was a start. And from that we got access to a second building that was part of the hospital and owned by the Order of St John at that point, and a second vehicle. So, we had two vehicles and a meeting room there, and that really was the team’s base for a lot of years, right through until the mid [19]90s, and was, in fact, where we worked out of, and effectively too. So that was my first contact with the Order, basically because Bill [Marshall] had managed to get a contact within the Order who was able to provide us with accommodation at that time.

Subsequent to that [the] connection with the Order really sort of grew and developed, and as the years went on, I think the Order obviously decided that Mountain Rescue was a very worthy cause in terms of their objectives, and Bill [Marshall], and subsequently myself when I took over as Team Leader in 1993, were involved in supporting the Order, going out to other Mountain Rescue Teams and basically trying to persuade rescue teams that having a connection with the Order would be a really beneficial thing for them, because out of that, the likelihood was they were going to get support.

Fundamentally, the Order and its continued support of Mountain Rescue and the continued support of the Aberdeen team, I think, was a huge factor in taking Scottish Mountain Rescue from what was, I think, a very ad-hoc type of organisation, and giving them the equipment to actually become much more professional than what they did. And the Order has continued to do that over decades, in fact, and they’re still doing it to a certain extent. I think there are a lot of Mountain Rescue Teams in Scotland who would not be in the financial position they’re in now, and have the equipment and the vehicles and the accommodation that they have got, if it were not for contributions made by the Order.

A new base for the Aberdeen Mountain Rescue Team was opened in 1997. Two smaller bases were completed for the Skye Mountain Rescue Team in 2000, one each side of the Cuillins. By 2007, bases had been built for the Arrochar, Dundonnell, Lomond, and Moffat teams and an existing building had been bought for the Oban team. Additional help has since been given to Arran, Assynt, Tweed Valley, Galloway, Kintail, Lochaber, Ochils, Tayside and Torridon teams. Activities are wide-ranging as teams are often called out to help find vulnerable individuals at risk of harm or self-harm, or hillwalkers or injured climbers missing in rural or remote areas, including moors and coastal areas, and may involve working with HM Coastguard, RNLI, Police Scotland, or SARDA (Search and Rescue Dog Association). Searches and rescue operations may involve crashed vehicles or aircraft.

In the Highlands, St John Scotland has made generous contributions to

search and rescue operations, as explained by Alex Craib:

If I remember correctly, every Mountain Rescue team in the Highlands of Scotland were given vehicles. Either Land Rovers specifically manufactured and kitted out for Mountain Rescue, and also ambulances which are designed specifically for travelling on the terrain. The Dundonald Rescue Team were given four bases because they cover such a big area. They found that with the time lost in travelling to the central base to pick up the gear, and then travelling out to the location, they were losing so much time there that it is more advantageous to have separate bases. So, they have four bases across Ross-shire that are all kitted out. When the call goes out, they go to whichever base is closest to the incident. Aviemore Mountain Rescue Team, we were involved in their new base, quite a number of years ago now. They purchased a church, and I was involved in it, from the Order, in the kitting out, and making the church an appropriate place for the Mountain Rescue base. So, all the Mountain Rescue Teams in the area have support.

By 2016, St John Scotland reported that it had been the single-biggest supporter of the voluntary mountain rescue movement in Scotland, investing over £3.5 million and donating bases to 11 of the 27 teams and at least one emergency vehicle to every team. St John Scotland has since transferred ownership of the bases to the teams, though they still proudly display the St John Scotland logo. As well as bases, St John Scotland began a rolling programme of providing vehicles to Mountain Rescue teams and all teams in Scotland have taken delivery of a new and updated vehicle to be used on callouts. St John Scotland’s support for Scottish Mountain Rescue continues.

Kev Mitchell, Vice-Chair of Scottish Mountain Rescue, wrote to describe how St John Scotland has supported Ochils Mountain Rescue Team:

The Ochils MRT first received support in the shape of a bespoke Land Rover in 2001; this replaced the gas guzzling, second hand V8 Land Rover we managed to buy from our somewhat more affluent neighbours, the Lomond MRT!

At that time, the team was based in a double sectional garage behind the council nurseries in Menstrie; this was basic to say the least, without running water, toilet, and with four plug sockets to charge the torches! In 2006, the team started the journey to build a purpose-built Mountain Rescue Post, and due to a large number of setbacks and problems, the new post was [finally] opened by HRH The Duke of Gloucester in 2010, with the build costs fully met by the Order of St John.

The new post has completely transformed the way the team operates and has allowed us to be able to set up a control and communications base, facilities to run courses… and we will host a Scottish MR equipment course in February. In addition, we have a never-ending programme of visits from schools, youth groups, community groups and hillwalking clubs, which allows us to promote our message of hill safety and promote the work of Scottish MR and [St John Scotland]. The post also allows us to put in place admin and recording systems, which would have been difficult without a permanent water-tight base!

The post has enabled the team to develop in a more effective, and professional manner and has allowed us to serve our community better, and to provide not only Mountain Rescue assistance, but also community resilience assistance to local communities.

MOUNTAIN SAFETY

Additionally, since 2015 St John Scotland has also worked in partnership with Mountaineering Scotland to provide mountain safety training to young people across the country. The St John Scotland Mountain Safety Instructor programme offers free training to university and college mountaineering groups throughout the year. The aim of the training is to ensure that young people coming into the sport and developing an interest in outdoor pursuits can do so safely. Courses are delivered in real life conditions, on a range of terrain and in all weathers, to equip young people with practical skills that will stand them in good stead for life.

Photograph courtesy of John Davidson

INSHORE RESCUE BOATS

St John Scotland’s support for outdoor safety and rescue extends beyond the hills, and in 2006, its commitment was further extended to lochs, with a major donation to a new rescue boat for Loch Lomond. The Arctic 22 was a Rigid-Hulled Inflatable Boat, which cost £108,000, and St John's donation of £32,000 made it the main contributor. As a result, the boat carries the St John name and logo. With two 115 horsepower engines and a top speed of 45 miles an hour, the St John was designed specifically for the Loch Lomond Rescue Boat Committee and includes a large deck area for stretchers and fire-fighting equipment. Additional donations from St John Scotland have since contributed to the boathouse at Luss, which provides much improved training, changing and drying facilities for the crew.

In 2004, St John Scotland funded a Land Rover for Nith Inshore Rescue. This search and rescue unit is based just south of Dumfries on the estuary of the River Nith. It was formed in 1982 following several fatal incidents in the area which highlighted the need for rapid response. The main areas of operation are the hazardous tidal stretches of the River Nith and the Solway Firth but rescues are deployed to other rivers and to inland lochs. The Land Rover was equipped with a radio, first aid equipment and, on the roof, an 8-foot inflatable dinghy with an outboard engine. The all-volunteer crew have saved adults and children who were missing or cut off by the tide or floods or otherwise at risk; animals have also been saved. The unit operates closely with the police, HM Coastguard, RN and RAF helicopter crews, the RNLI and also with Mountain Rescue teams.

THE SEARCH AND RESCUE DOG ASSOCIATION (SARDA)

The Search and Rescue Dog Association arranges the training and provision of dogs for search and rescue operations. It works very closely with Mountain Rescue teams and other emergency organisations and is affiliated to Scottish Mountain Rescue. St John Scotland supports the association by providing equipment and meeting the modest running costs of its call out system.

The Search & Rescue Dogs Association, SARDA, we support them as well, and they work very closely with the Mountain Rescue Teams; we presented SARDA with a new trailer [which] was very similar to a base, all kitted out with their equipment, and when the rescue was required, the trailer would be taken to the area. They gave us a demonstration to see the dogs at work and it was absolutely fantastic. We had no idea how a dog would work on the hills, but when they had the harness put on, they changed into a working dog. It was really fantastic and when they found the patient, or the person who was lost, their reward for that was to play with their particularly favourite toy. So, they would get to play with the toy for a few minutes having achieved their objective, and when that was taken away and the harness taken off, they were family pets again. It is absolutely fantastic; we are very happy to support this service.

THE AIR WING

The St John Ambulance Air Wing was formed in 1972 to provide a volunteer service for the rapid transport of organs, drugs, blood supplies, and patients in emergencies when other means are not available. In Scotland, the Air Wing was operated from Dundee Airport and manned entirely by volunteers. The pilots in the scheme were St John’s auxiliaries who, with the establishment of the St John organisation in Angus, became members of St John Association of Scotland.

The function of the air wing was to assist ‘by any possible means’ in lifesaving or emergency missions in the UK or abroad that were within the scope and ideals of St John Ambulance Association. By 1980, there were over 100 pilots in the UK with more than 60 single and twin-engine aircraft. The majority of pilots were formed into groups covering the whole of the UK and were able to fly to and from small airfields and landing strips as well as the major airfields. The majority of flights were for the carriage of transplant kidneys at night, though there was also a demand to carry patients, and the Air Wing also supplied medical and nursing air attendants and medical equipment.

Air Wing pilot Sandy Middleton and his daughter Fiona, who was also a pilot and joined her father on several flights, became used to getting called out at the most inopportune moments:

After more than 20 years of service, Air Wing ended in June 1993.

SUPPORTING LOCAL CAUSES

With few services of its own at that time, as well as supporting Mountain Rescue teams, St John Scotland’s volunteers focused on raising money to support other organisations making a difference in their local area. Through the 1980s, 1990s and into the 2000s, hundreds of causes were supported, making a real difference to individuals and communities across the country.

Douglas Dow discussed some of the projects supported by the Dunbartonshire Area during his time with St John Scotland:

The first one was Arrochar Mountain Rescue, then we took on several others, one of which was support for the Loch Lomond Inshore Rescue Boat, called ‘St John’, which is based at Luss at the moment, which is very active indeed. Then we also supported and continue to support the St Margaret of Scotland Hospice in Clydebank, which is run by a Roman Catholic order of nuns. Sister Rita is in charge there and it’s open to all; it’s not just for Roman Catholics, anybody can go to it, religion or no religion, and it’s a really lovely environment for palliative care. It relies wholly on funds, which are raised privately. The fourth one is at the Vale of Leven Hospital in Alexandria. There is a special unit called The Acorn Unit, which is a unit that is devoted to the treatment of children, normally young children, with multiple disabilities, and the objective is to facilitate their treatment in such a way that they can go and get several or all of their disabilities treated at the same time, so they don’t have to go to different hospitals for their treatments. It’s an NHS hospital but they are always needing a little bit of help. And some of the specialists they have, we’ve funded them going on courses for their speciality, which, because of the extra expenditure, the NHS would have liked to have put them through but couldn’t, because of the money. We can do that.

Asked how she became involved with St John Scotland, Gwen Fullerton’s daughter recalled

It was through my Dad; he was involved through the work he was in. He would say, ‘Come along and see this’, and ‘Come on, we’ll go up for a run and we’ll help these people’, and it was through the charity helping the Chernobyl children, over having a holiday and getting health treatment and things, and we would go along to some of their social events and just be there with the children. And a couple of times, we went swimming and things like that, so we’d be helping the younger ones in and out the pool and sometimes learning to swim. So that was my first one. Then bucket rattles at the Caley Thistle football ground on cold Saturday mornings!

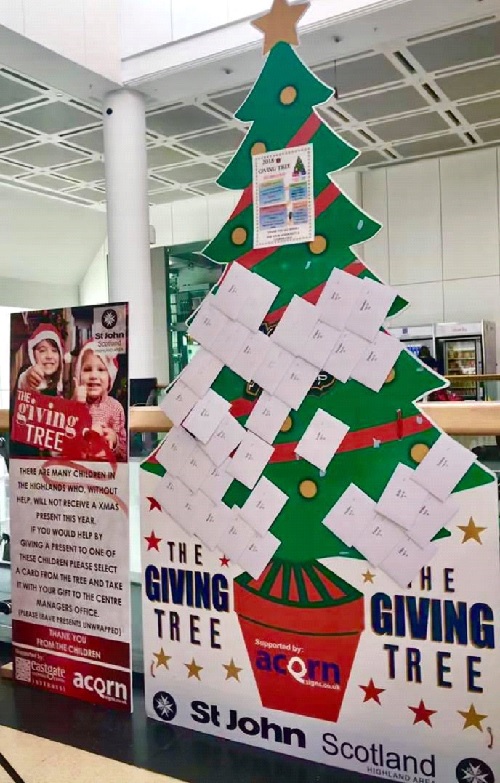

The Giving Tree is an idea that I saw in Aberdeen… I was intrigued by the idea so I went to look and there were these little cards, and the idea was that you would take a card and buy a gift for the child on the card. For instance, if it was a ten-year-old girl, you would buy a gift for a ten-year-old girl, wrap it and take it to the manager of the centre, and it would be distributed to a child in care. So, when I came home, I mentioned that to the Chairman at the time and we agreed that it was a good idea… So, we organised it the first year and we had thirty-five children. We had a tree made up by a friend of ours who had a sign company, they made up an imitation Christmas tree. We put that up in Eastgate Centre in Inverness. The Social Work Department in Inverness gave us names of children and we attached these to a Christmas card and put it on the tree and the public would come along, take a card and buy a gift, go to the Eastgate management, and we’d deliver it from there. My wife and I have maintained that every year since and we had agreed recently that this was our twenty- first year but on looking through some old paperwork I discovered that it was twenty-six years and in that time it’s grown huge.

We do carry out a lot. The one that people may not have heard of was that at one time there was an athlete in Aberdeen called Kenny Herriot, and Kenny was an ex-Army PE Instructor, and his motorbike came to a stop and toppled over onto him. It was only moving two or three miles an hour and he thought, ‘Oh well, that’s not a problem’, until he tried to move and suddenly found that he couldn’t. However, nothing ventured, nothing gained, he went through his rehabilitation and realised that he wanted to do things still, so he took up wheelchair racing, and St John in Aberdeen purchased a brand-new racing machine for him to compete in and he did wonderfully well. He had to go to Denmark to get the machine made and fitted because it had to be high quality for him to be able to compete properly, and on his two large wheels was ‘The Order of St John’, and he did quite a bit of motivational public speaking and was brilliant. That was a nice one for us to do. The Cancer and Leukaemia Action in Aberdeen, known as CLAN, they required a vehicle and we provided that. We also helped provide for the Portlethan Ambulance Service. It’s not an ambulance as such, it’s a patient transport vehicle for need in the community. One of the main things it does is to pick up prescriptions and deliver it to people who are stuck at home and can’t get out. So, we helped them with that… There is also the Aberdeen Sitter Service, which is 25 plus years we’ve been supporting them, although I haven’t seen much of them over the recent past.

SEAGULL TRUST

1979 was the year that St John Scotland moved into another new area of assistance. The Reverend Dr Hugh Mackay founded the Seagull Trust in Scotland, an organisation which provides cruising on Scotland’s canals for people with disabilities. With his guidance and drive the Edinburgh Committee agreed to provide a specially adapted barge, which was named the St John Crusader. This was berthed on the Forth and Clyde Canal at Ratho, near Edinburgh.

I was living in Edinburgh at the time so I became involved with the Edinburgh Branch and helped out with various things, can collections, the annual sale. The Edinburgh Branch at that time, they’d bought an old barge, and the prisoners at Saughton Prison had done it up and it was presented to Seagull Trust up at Ratho. The idea was to take disabled people and children for a cruise along the canal at Ratho, so I got involved with that and I quite enjoyed that. It’s different, I sailed anyway, but it’s entirely different with these barges. The steering can be quite difficult because a barge’s pivot is in the centre, and you have to actually go past a corner before you turn the rudder to get successfully round. It took a wee bit of getting used to, but I enjoyed that.

We have supported the Seagull Trust which does cruises. There is one in Inverness and one down towards the Central belt. We have given the Seagull Trust support over the years. Our ex-Provost Bill Fraser was a Chairman of the Seagull Trust in Inverness. Seagull have a boat that takes tours up and down Loch Ness and they take tours of vulnerable people, disabled people, and people who live in care homes. In fact, Ramsay [McGhee, St John Scotland Highland chair] was a crew member.

Support for the Seagull Trust continued, with a second boat, the St John Crusader II, gifted in 1996.

ST JOHN TRANSPORT SERVICE

In the late 1990s, as well as growing its support for Mountain Rescue teams, St John Scotland used some of its funds to help other charities buy much-needed vehicles they could not otherwise have obtained so quickly, if at all. The vehicles were mainly minibuses; in many cases specially adapted to meet the particular requirements of those who use them. Among those organisations to benefit from the scheme were:

- Acredale House, Bathgate

- The Arbroath Town Mission

- The Bannockburn branch of Riding for the Disabled

- The Berwickshire Association of Voluntary Services (‘Berwickshire Wheels’, pictured below)

- Borders Disability Forum (‘Gala Wheels’)

- Braendam Family House

- Carberry

- Disability Sport Fife (pictured below)

- The Dumfries Community Day Centre for Older People

- Edinburgh Zoo

- The Eric Liddell Centre, Edinburgh

- Erskine Hospital, Bishopton

- Fairbridge

- Macmillan House Perth

- The Marie Curie Cancer Care Hunters Hill Centre

- Mental Health Aberdeen

- OASIS Care, Perth

- The Ogilvie Centre Dundee

- Penumbra

- The Portlethen and District Community Ambulance Association

- The Prince and Princess of Wales Hospice, Glasgow

- PUSH, Edinburgh and the Lothians

- Sense Scotland

- Strathcarron Hospice, Denny

- Sue Ryder Home

Neo-Natal Ambulance

One major exception to St John Scotland providing minibuses was its support for a new purpose-built ambulance for the Scottish Neonatal Transport Service (SNTS), which took over a year to design and build. The fully equipped ambulance, which cost £212,000, was specially designed for the SNTS and at the time of manufacture, was the most sophisticated of its type in Europe. This was a matched funding project between St John Scotland’s Glasgow area and the charity’s national funds. St John Glasgow put to good use monies received from a bequest by the late Walter and Doreen Crichton.

We never ran ambulances, although we have provided an ambulance. One of many things that I was very pleased to be involved with was the presentation of the Neo-Natal ambulance at Glasgow around the year 2015. It cost around £140,000 and this was to treat babies, mainly recently born babies, who couldn’t take the risk of being put in a helicopter for the pressure on their heads. So, they needed a vehicle to take them that would have the equipment of an operating theatre within the vehicle, and it was done for two children at one time, and for the outlying areas, and take them to hospital in Glasgow. So that was a terrific thing. You save lives there, and we must have saved quite a lot of lives. That was a great thing.

BLOOD TRANSFUSION TRIAGE SERVICE

More recently, in response to the Covid 19 pandemic, St John Scotland actively sought ways to help the public, and began to support the work of the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service (SNBTS) by volunteering at blood donation sessions around the country. Alex Craib describes how this was implemented in Moray and the Highlands:

Recently, we have been involved in the Blood Transfusion Triage Services, so our two volunteers from Forres and Elgin got involved there with a volunteer from the Grantown area. The Chairman, [myself] and another volunteer get involved in activities outwith the Inverness area. We do the triage, so we meet the donor at the door; we have a list and a timed appointment, so when the donor comes, we mark them off as having attended. We take their temperature, and we ask fairly generic questions about their health - if they’ve got a high temperature; if they’ve had a continuous cough recently; if they’ve had Covid, or any Covid symptoms. Once we’re satisfied that the requirements have been achieved, we then introduce them to the receptionist and the donor then goes into reception, and into the system from there, where there are more detailed questions; but we ask generic questions just to make sure they haven’t had Covid and they are safe to enter the building. It’s a very satisfying time to be in the system there.

ST JOHN SCOTLAND ABROAD

ST JOHN EYE HOSPITAL, JERUSALEM

The St John of Jerusalem Eye Hospital Group is a subsidiary of the Order of St John, and all St John organisations support its vital work.

Founded in 1882, the main hospital in East Jerusalem has been operating for 140 years. The hospital is the main provider of eye care for Palestinians in East Jerusalem, and sees many of the most complex eye cases from across the oPt (Occupied Palestinian Territories), which are referred to them from medical centres across the West Bank and Gaza. The St John Eye Hospital has a large outpatients department, specialist eye units, operating theatres and 24-hour eye emergency services.

The St John of Jerusalem Eye Hospital Group is the only charitable provider of expert eye care in the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem. Supported by St John organisations and individuals across the world, the hospital provides sight-saving eyecare to thousands of patients each year, regardless of ethnicity, religion or ability to pay. In the past, donations from Scotland to the hospital in Jerusalem came from individual members, and from St John Scotland Committees and Associations. The original aim, in the 1940s, was to send at least £100 a year to Jerusalem, a fairly substantial sum in those days.

Now, St John Scotland supports the work of the Eye Hospital through annual grant funding for key pieces of work, most recently supporting outreach clinics which reach the most vulnerable patients who have least access to healthcare. St John Scotland was also the major donor to the Hebron hospital, part of the Eye Hospital Group which opened in 2015. This facility was built to better serve the population living in the West Bank and has greatly improved the accessibility of services in the area.

Ian Wallace is a former Hospitaller for the Order of St John in Scotland – traditionally, the link between the organisation and the Eye Hospital. He recalls how he was chosen for the position:

One of my fellow Chapter (Board) members was, of course, the then Hospitaller, Dr John Calvert, who was the General Practitioner down in Stranraer, and on his death, much to my surprise, I was asked if I would take on the role of Hospitaller. After I’d done that for a spell, I was promoted to a Knight of the Order. So, I was very lucky. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of ‘Imposter Syndrome’, but I think many of us have this feeling that , ‘How on earth did I get here?’ I’m sure some people think, ‘I’m in the right place, I jolly well ought to be here’, but most of us, I think, are slightly surprised to find ourselves in a particular place, I certainly was. One of the great joys of being Hospitaller was of course that I was expected and did go to visit the Eye Hospital in Jerusalem on a number of occasions, and I was also involved in making some quite important financial decisions from Scotland. Particularly, one I’m very proud of on behalf of the Scottish Priory is the funding we were able to give for quite a big outreach building for the Eye Hospital in the town of Hebron, which is south of Jerusalem where there’s a day clinic, at which there’s things like cataract surgery. Laser surgery for eye disease was carried out. And Scotland was a major contributor to the funding of that building, and the [then] Prior, Mark Strudwick, and I, and others, were there at the opening of that building. It was a really great pleasure to be involved in.

Ian went on to explain what kind of people received treatment at the Eye Hospital:

[The] patient population is pretty much exclusively from the Palestinian community, who of course are not cared for within the Israeli community. The Israeli hospitals are excellent, really good, but the Eye Hospital has continued its tradition of treating eye diseases; and it’s not just the hospital, which is in East Jerusalem, but there is the day hospital I’ve already mentioned in Hebron. There is a really big hospital in Gaza, which of course, is a very, very hazardous place, and we try to deliver care and various outreach clinics throughout the whole of the West Bank. So, it’s a very extensive service which is provided. The reason it’s eye diseases, is, when the original hospital was founded back in the 1880s, the main eye disease was probably infective trachoma, which is common in hot countries; now the majority of eye disease is either diabetic, and diabetes is very common in Palestinian population, cataract is common in all ageing populations, and congenital eye disease. Then of course, the other big problem is trauma, which unfortunately is rife in the Holy Land from time to time, particularly in Gaza.

Ian added that the Eye Hospital in Jerusalem is a purpose-built building in beautiful surroundings. The hospital is staffed by both Christians and Muslims, though the majority are Palestinians who have been trained as doctors, nurses, and administrators. They are assisted by specialists from Europe who visit and teach or carry out specialist surgery. The overwhelming feeling is that of a group of people from very different backgrounds with one objective - to deliver an excellent service, and this is recognised worldwide.

Another [memory] is, they had a big fundraising event one time I was visiting, and the hospital is built around a beautiful open courtyard, lovely magentas in red and orange flowers, sitting there in the twilight, and everybody, people from all over the world who support the Eye Hospital, from America, from Australia and other parts of the world, and just this sense of being part of this worldwide community supporting this particular endeavour.

ST JOHN MALAWI

Since 1988, St John Scotland has supported its sister organisation, St John Malawi, with a community-led healthcare programme to improve the lives of children and families living in one of Africa’s poorest countries.

Malawi has a poor life expectancy and high infant mortality, and it ranks lower than any other country in which St John operates. In addition to first aid training and support, St John Malawi runs a Primary Health Care Project. Begun in 1988, the project helps prevent illness through education and immunisation, with particular emphasis on the health of young children. The volunteer Community Health Workers also provide other medicines and training in the home-based care of seriously ill people. They work in the most densely populated townships of Malawi's commercial capital, Blantyre, where living conditions are very poor. Since 2004, St John Scotland has provided funds to help meet the modest running costs of the project, allowing the number of workers to be increased.

Former Chief Executive of St John Scotland, Richard Waller, recalls how the organisation first became involved with Malawi:

Our partnership with St John Malawi is related to the reorganisation of the Order internationally, because that certainly increased the awareness of us in Scotland about the existence of St John overseas. And there was a lovely New Zealander called John Strachan, who had been the Chancellor, effectively Prior, of St John New Zealand, and one of his roles in the early 2000s, as the Order’s Sub Prior, was to act as a link between the governance of the Order internationally and the Associations. So, he travelled extensively and he noted that whereas the other Priories had developed links with Associations, I think as much as anything through helping them with their first aid equipment or training, because obviously they’ve got a lot of first aid common ground, Scotland hadn’t done anything like that at all. For example, England had links with multiple Associations and sent them equipment, and similarly for Canada, and for Australia with Pacific Associations.

John suggested it was something that would be helpful for both us and an Association, and he suggested Malawi because of the obvious Scotland-Malawi links. But he said, ‘Don’t think just because I’ve suggested Malawi, that you have to go with Malawi, it’s up to you. If there’s some other Association that doesn’t have a link which might suit better, you can go with them if you want’. Anyway, I was going to a Priory Executives’ meeting in South Africa and it was suggested that I make an exploratory visit to St John Malawi on my way back. I set this up with Dr Dick Chilemba, who was the Chair of the Association, and Tom Kanyuka, who was the Secretary and said, ‘We have a possible link in mind. Would you be happy and can I come, and are the dates all right?’ and so on and so forth. And they said, ‘Yes’, so I visited for a couple of days. And I said beforehand, ‘Look, I don’t want to raise your hopes, because Scotland might not take up the idea of a link with an Association at all, or it might take it up but not with Malawi, so please don’t get your hopes raised. And please, I would suggest, keep it very tight to just the two of you and whoever else on your Council you might want to bring into your confidence’.

So, on a Friday, I landed at Blantyre airport, just! A very dodgy landing during a huge tropical storm when there just happened to be a gap in the clouds and blue sky. It was like the eye of a hurricane! And we landed, and the water on the runway was so deep that we had to take off our shoes and socks and even roll our trousers up a bit. And there was Tom, who was then, the Chairman I think, of Malawi Airlines. Anyway, he was there, so he and I go in through the VIP bit of Blantyre Airport, which only means you use this door instead of that door; you don’t get champagne or anything! But it was very nice, and Tom took me to my hotel and we had a chat when we got there and he said, ‘We’d like to take you to show you our headquarters tomorrow [which was Saturday], would you like to see them?’. ‘Yes please, I’d like to.’ ‘Well, I’ll pick you up at 9 o’clock and we’ll go off and do that’.

So, Tom picks me up, we drive off to their headquarters, and, lo and behold, there, of course, are all the volunteers! ‘Right, this is Richard Waller from St John Scotland who’s come to visit us, and Richard, would you like to tell us about your visit and St John Scotland?’. So, I did that, through an interpreter because the volunteers speak Chichewa, the local language. Anyway, did that. A clever move by Dick and his Council, but it was delightful because, as it subsequently transpired, a link with them fitted like a hand in a glove; it was just so perfect for us and for them. We asked, ‘How can we help?’, and what they really wanted was funding for their Community Health Workers, who are volunteers who go round the townships around Blantyre helping with illness prevention and healthcare, and particularly for expectant mothers, babies and children - weight monitoring and that sort of thing and also, importantly, immunisation and other provision of medicines. They also provide training in how to look after people who are ill in their own homes – Home-Based Care.

So, we helped with an annual grant, from 2004, and this enabled them to double the number of volunteers to their target number of 60. And since then, we’ve helped St John Malawi in other ways, of course, as well as other Associations, in Africa and elsewhere.

As well as long-standing support for the Blantyre project, in 2018 St John Scotland was granted funding from the Scottish Government to support a new project based around the Lilongwe area. The five-year programme is helping thousands of people improve their health, and will reach 57,000 people at home, including more than 10,000 expectant and new parents. It is hoped the programme, which has been funded until 2023, will also contribute to the sustainable development of Malawi’s health sector in the long term.